Disunion Runs Deep

Slavery is the Union’s original sin. It set the stage for two centuries of polarization in U.S. politics

Read

America’s U.S. Constitution was supposed to unify the new nation and help avert a civil war over its thorniest source of division: slavery. Oops! In retrospect, that charter proved much too ambiguous, lending itself to both proslavery and abolitionist causes. In this season’s premier, historian Liz Varon discusses the deep roots of polarization in the United States — with Will, Siva and an auditorium full of their students. The Union may have survived, Varon tells us, but its bloodiest war still echoes.

An expert on the Civil War and its aftermath, Varon contends that the motivations driving right-wing extremism are born of the same impulses that led to division and violence during the war and in the wake of a failed Reconstruction in the South. She says Americans today should be wary of political attitudes that demonize reformers, instigate chaos, and purposefully confuse the effects of polarization with their causes.

Meet

Elizabeth Varon is the Langbourne M. Williams Professor of History at the University of Virginia, where she teaches about intellectual history, the American South, and the role of women in the context of the Civil War. She is the author of numerous books, including the highly decorated Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom at the End of the Civil War (Oxford University Press, 2013). Her latest is Armies of Deliverance: A New History of the Civil War (Oxford University Press, 2019). On occasion, Varon offers keen insight on historical parallels with the present, in her contributions to the Washington Post.

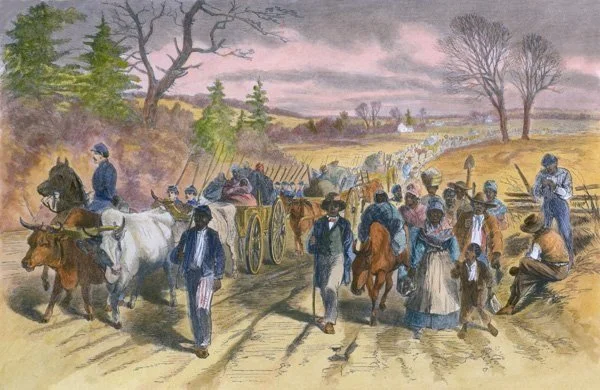

Armies of Deliverance offers a fresh look at America’s darkest period, taking into account the narratives of both black and white soldiers in the Civil War, as well as citizens on the home front. On one side, Varon writes, the Union fought for liberation and deliverance of its Southern brethren. On the other, Confederates saw that effort as a war of conquest.

In the Post last June, she identified parallels between allegations of voter fraud in 1860 and 2020. In both cases, racial animus and conspiracy mongering played a role. “The election deniers of 2020 need not be aware of this rather obscure history to be shaped by it,” she writes.

Indeed, Donald Trump’s campaign tactics come “straight from Southern enslavers,” Varon has said. These included suppressing the votes of black people, intimidating the press, inciting terror, and claiming that activists were causing unrest rather than responding to injustices.

Varon contributed a chapter in Charlottesville 2017: The Legacy of Race and Inequity, a volume that offers memories, reflections and historical context on the violent protests that erupted in her hometown that summer.

In seeking to remove Confederate statues from Charlottesville’s landscape, Varon argues, city leaders are not “obscuring” history but paving the way for a more nuanced understanding of the past. The stories of local black leaders, Varon says, belong on the tapestry of the region’s history, which “myth and dogma” have thus far tarnished.

Learn

Partisanship, Varon warns, can be a harbinger of mutually assured destruction. Witness Politico’s recent riff on this nuclear imagery, in pointing to escalating tensions over Donald Trump and Joe Biden’s mishandling of classified records.

In the early republic, political opponents often accused each other of “moral failings.” It’s another trope that hasn’t gone away. Last year, the Pew Research Center found that the share of Republicans who believe Democrats to be more immoral than other Americans rose from 47 to 72 percent during the Trump administration. The same statistic for Democrats went from 35 to 63 percent.

As you’ll hear on the show, African Americans were always at the forefront of abolitionist movements and the “protest tradition” in U.S. politics. These figures included the poet Phillis Wheatley (a central figure in the Black Prophetic Tradition) and the Rev. Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

It’s not a monolithic bunch. An important fault line in that tradition was whether to read the Constitution as irredeemable proslavery or a beacon of liberty. Frederick Douglass leaned on its latent abolitionism, while William Lloyd Garrison called it “an agreement with hell.”

Historian Allen Guelzo takes a stab at imagining what might have happened had Abraham Lincoln not been assassinated in 1865 — a question posed by one of our students on the show. Guelzo imagines Lincoln agitating for universal suffrage, supporting land ownership in the West for newly freed families, and encouraging the rise of pro-Union leadership in the South.

Writing for Time Magazine in 2019, Don H. Doyle underscores the point that a quarter of the Union Army was made up of immigrants, and another 18 percent were first-generation soldiers. Indeed, he says, many demonstrated their patriotism by leaving steady jobs to fight in the war.

“You’re the real people,” President Trump assured his supporters before they stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. This rhetoric harkens back to successionist discourse of the 19th century — and to Nazi Germany. In each case, essayist Nina Burleigh writes, nativist extremists claimed working-class origins for movements largely bankrolled by the wealthy.

We love to bash the oligarchy on Democracy in Danger. Check out “We the Entrenched” with Joseph Fishkin and Melissa Schwartzberg, for a critique of the constitution in light of the monied interests it served.

And for more on the perils of toxic partisanship — and how to counteract it — listen to last season’s finale with Anand Giridharadas, author of (among other things) Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World.