In Ukraine, Hell — and Hope

Five Russian soldiers squatted for weeks with a Ukrainian family, unwelcome. What they learned is telling.

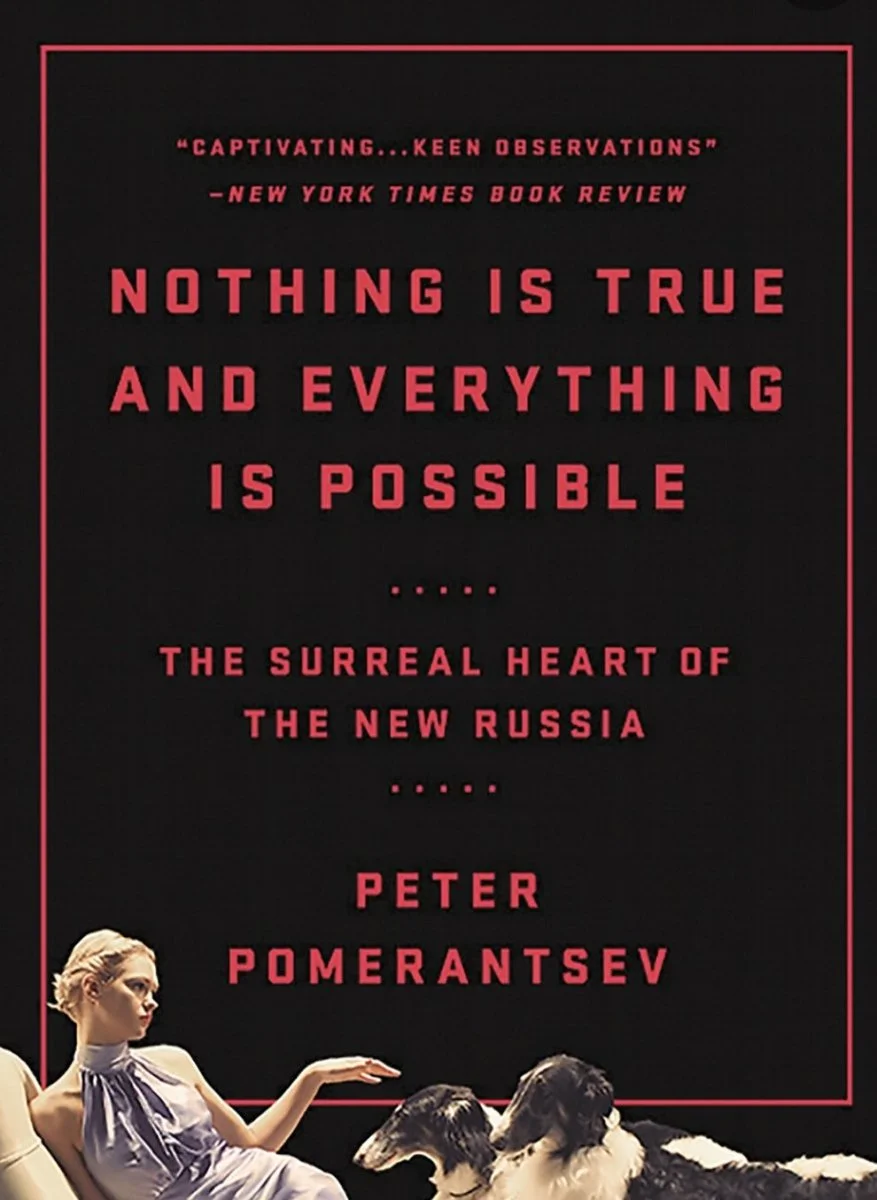

Russian forces have pulled back from around the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv. They’ve left the country’s second largest city, Kharkiv. But farther east and south, the fighting has intensified, and the civilian death toll is mounting. How will this war end? What will remain of Ukraine? And are European powers doing enough to punish Russia for its devastating invasion? Journalist Peter Pomerantsev — recently back from covering the conflict for the Atlantic — helps Will and Siva parse a complex picture.

Pomerantsev tells the story of one Ukrainian family who survived several weeks confined in their cellar with a handful of Russian soldiers. Slowly but surely, the Horbonos family chipped away at the lies their uninvited visitors had swallowed from their own government. This story serves as a kind of allegory for how Russia might ultimately lose the war, Pomerantsev says, despite its military might and its domestic propaganda machine. In the meantime, he argues, Western nations must maintain a unified front, in their sanctions and their rhetoric, and make ready to help Ukrainians rebuild their country.

Heard on the Show

At the top of this week’s show, you’ll hear audio from multiple news sources, including reports from NBC in Severodonetsk and Luhansk; CNN in Kyiv and Moscow; UN Radio in Poland; the Guardian in Ukraine and Russia; and ABC in Kharkiv; as well as a France 24 broadcast in March analyzing Russian dissent. We also included a bit of Zelensky speaking, through a translator, in a virtual address to the World Economic Forum in Davos, on May 23.