No Good Reason

America incarcerated well over 100,000 people for years without cause.

Read

After the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, a racial panic took hold over the United States and its leadership. And President Franklin D. Roosevelt — otherwise known for the progressive policies of his New Deal — approved the mass removal and confinement of Japanese American families, on scant evidence of disloyalty. Our team discusses this shameful chapter in U.S. history, and its legacy, with a daughter of two erstwhile internees and one of the world’s foremost students of the era.

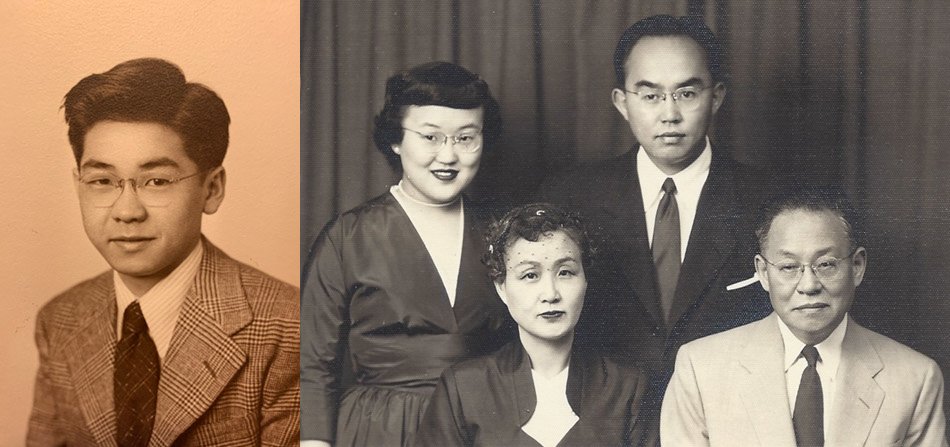

Education professor Karen Kurotsuchi Inkelas and historian Greg Robinson help us explore the trials and paradoxes of Japanese American internment during World War II. As children, Inkelas’s parents were forced to leave California and live in “relocation centers” — really, concentration camps — in other states.

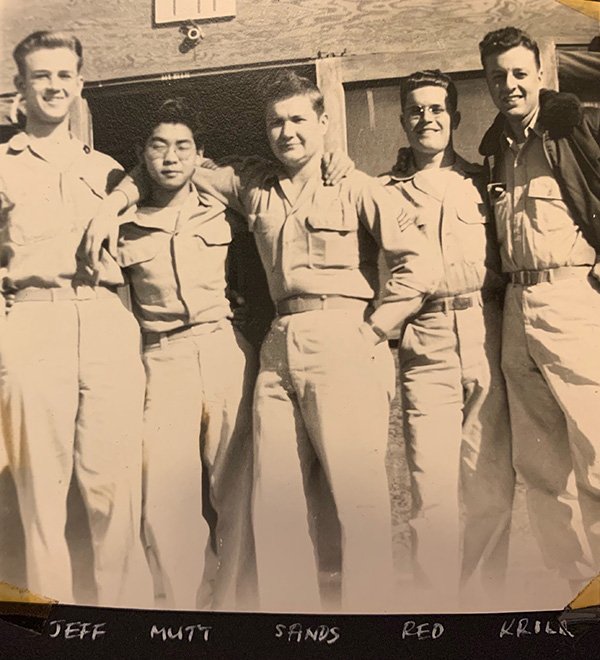

Like most of the 127,000 people interned for some three years, Inkelas’s parents were U.S.-born citizens. Before the war’s end, her father would have to don a uniform and face another relocation: to the Pacific theater. A generation later, Inkelas says, she would search for her roots in Japan, where she came to realize that identity is not as simple as where your family comes from.

Robinson has written for decades about the Japanese American experience, especially during and after the Good War. He calls Japanese confinement “a tragedy of democracy.” As he tells Will: “In a war fought for democracy, and the preservation of democracy against fascism, a democratic country and the leader of the forces for good in the world actually rounded up its own citizens, really out of no reason but wartime hysteria, political opportunism — very obvious flaws.” This, despite the fact that even J. Edgar Hoover’s notoriously paranoid FBI did not consider Japanese Americans a threat.

Meet

Karen Kurotsuchi Inkelas is a professor of education at the University of Virginia’s School of Education and Human Development. She studies how college affects students, especially those from minority groups. Inkelas directs a project called Crafting Success for Underrepresented Scientists and Engineers, which tries to close the achievement gap in STEM fields. Her other research interests include living learning communities, mindfulness and the conditions for flourishing among first-year university students. She is the author of Racial Attitudes and Asian Pacific Americans: Demystifying the Model Minority (2006, Routledge).

Greg Robinson teaches history at the University of Quebec in Montreal. His work focuses on 20th-century America and he chairs the university’s research program on immigration, ethnicity and citizenship. Robinson is the author of numerous books, including By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (2001, Harvard University Press); A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America (2009, Columbia University Press); and After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics (2012, University of California Press, 2012). He also writes a column, for Nichi Bei News, called “The Great Unknown and the Unknown Great.”

Writing for Nichi Bei in 2017, Robinson discusses the importance of complementing archival research with the first-hand accounts. He recounts many of Japanese American postwar stories in After Camp.

While most of the communities dislocated during World War II hailed from the West Coast, Robinson has also documented “the astonishing history of Japanese Americans in Louisiana,” in an edited volume from the University of Alabama Press. He has also written about the very cosmopolitan Japanese American Committee for Democracy, active in New York City in the 1940s.

In “Writing the Interment,” from the Cambridge Companion to Asian American Literature, Robinson contemplates the literary afterlives of internees.

Americans of African and Japanese descent joined forces in standing up against FDR’s Executive Order 9066, which allowed for wartime removal and confinement. These groups continued to work together in the civil rights era. But in an essay for the 2016 edited volume Minority Relations: Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation, Robinson examines how that relationship shifted from solidarity to tension, as Japanese Americans prospered after the war. In 1988, the government provided $20,000 in compensation for the living survivors of concentration camps. The United States has never made financial reparations to the descendants of enslaved people.

Developing a sense of belonging in college is a challenge for all incoming students. In a 2007 study, Inkelas found that this struggle is especially pronounced for students who belong to racial and ethnic minorities.

Asian Pacific Americans in particular “feel threatened by both majority and minority groups in the college admissions process,” Inkelas writes in the Journal of College Student Development. At the same time, in a longitudinal study of Asian Pacific American undergraduates, she found that their participation in ethnic clubs and activities deepened their group commitments.

In Racial Attitudes and Asian Pacific Americans, Inkelas observes that APA students generally receive less attention in scholarship on higher education because of their “invisibility” in policy discussions.

Learn

In the late 19th century, relations between Japan and the United States seemed cozy enough. In 1884, just two years after Congress had adopted the Chinese Exclusion Act — prohibiting Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States — America signed a treaty with Japan supporting Japanese immigration and naturalization.

Less than a decade later, sentiments had begun to change. The San Francisco school board moved to segregate Japanese and Chinese students from their white counterparts. In a diplomatic exchange from 1907 to 1908, American and Japanese officials outlined a “Gentlemen’s Agreement” in response. The administration of then–President Theodore Roosevelt agreed to pressure California leaders to end school segregation, while Japan committed to limiting the immigration of laborers.

Fueled by white nativism, the Immigration Act of 1924 would supplant that agreement. Also known as the Johnson-Reed Act, that law banned all immigration from Asian countries — a policy that would remain in place until 1965.

Living mainly in ethnic enclaves on the West Coast, Japanese Americans faced racist and exclusionary attitudes long before the government forced them to move. Among their nemeses: the U.S. labor movement.

FDR’s order allowed the military to open concentration camps in far-flung states: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming. Download a complete map of confinement sites from the Japanese American National Museum.

A typist for the California Department of Motor Vehicles became an unlikely hero in the fight to end the government’s policy of internment. Mitsui Endo took her case to the Supreme Court and won — on Dec. 18, 1944. Still, splitting hairs, the court also ruled that mass removal itself had been constitutional, in the notorious case of civil rights activist Fred Korematsu.

Among critics of Japanese internment Eleanor Roosevelt stands out. While she never publicly criticized her husband’s decision to issue Order 9066, the First Lady privately pushed for closing the camps.

Tellingly, not a single Japanese American was convicted of spying or sabotage. Relocation and incarceration, meanwhile, proved to be an economic calamity destroying (in today’s dollars) some $3.64 billion of wealth they had achieved over decades, writes Alice George for Smithsonian Magazine: “Their businesses were hijacked by people eager to profit from their misfortune. As they prepared to reach the first stop in their odyssey — temporary detention centers — many were forced to sell property at bargain-basement prices.”

We asked both guests on this episode to compare current debates over migrants from Mexico and Central America with the history of FDR’s relocation centers. The Santa Barbara & Ventura Colleges of Law asked their students a similar question, in 2019. “The silenced history of those imprisoned after the bombing of Pearl Harbor is eerily similar to the separated families at the U.S. border today,” they wrote.

If you’ve been listening to the show since 2020, you know that humane immigration policy and resistance to xenophobia are crucial topics for us — and for saving democracy. Check out episodes like “Border of Cruelty,” “Census Division” and “Bittersweet Dreams” for much more.

Heard on the show

At the top of the show, you’ll hear a bit of Franklin Roosevelt’s famous address to Congress following the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor — “a date which will live in infamy.” Read the full text at the Library of Congress website.

We also scored the show with tracks from some of our favorite Creative Commons artists, in this order: Chad Crouch, with “Pacific Wrens” (2021); Pawel Feszczuk, with both “Monsters of the Past” and “A Chat by the Fire” (2022); Podington Bear, with “Lucky Stars” (2017); Kai Engel, with “Endless Story about Sun and Moon” (2015); HoliznaCC0, “Ugly Truth” (2022); and Lobo Loco, with “Pilgram Path” (2024). And, yes, it’s spelled Pilgram.

Bonus content

Listen to Will and Siva’s complete interviews with Greg Robinson and Karen Kurotsuchi Inkelas.

Transcript

Democracy in Danger S8 E7: “No Good Reason”

[THEME MUSIC]

[00:03] Robert Armengol: Hello, I’m Robert Armengol.

[00:04] Siva Vaidhyanathan: And I’m Siva Vaidhyanathan.

[00:06] RA: And from the University of Virginia’s Karsh Institute, this is Democracy in Danger.

[00:11] SV: We’ve been talking a lot this season about walls — both physical walls and the mental barriers that we carry through life — and the place of these walls in a democracy. Well, today we’re going to revisit a period in American history when thousands of people were taken suddenly from their homes. They were kept behind barbed wire. They were incarcerated for years. They were treated as enemies. And most of the country just sort of accepted it.

[00:39] Karen Kurotscuchi Inkelas: So, at some point, and I can’t remember exactly how old I was, but my parents sat me down and told me that they had been interned themselves, which I had no idea about. Frankly, if they hadn’t told me, I don’t think I ever would have known.

[00:54] SV: This is Karen Kurotsuchi Inkelas. She’s a friend and colleague here at the UVA School of Education.

[01:00] RA: Siva, you spoke with Karen, I know, about how her family were interned in the 1940s as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s war policy, right?

[01:07] SV: That’s right. We talked on a very personal level about that difficult moment and its legacy.

[01:15] KKI: So, my father was 14 and he was living in Northern California, and my mother was ten, and she was in Southern California when Pearl Harbor took place. So, when they were interned, they were kids. My mother’s side of the family went to Rohwer, Arkansas, which, you know, that’s a far cry from Southern California. And she would tell these fantastical stories about playing with crayfish and snakes and things like that in Arkansas she’d never seen in Orange County, California. And my father, his family was interned in Poston, Arizona. So, the high desert in Arizona, you know, again, very different from where he was.

[01:48] SV: Sort of the reverse of Grapes of Wrath — when Californians are pushed back to the middle of the country.

[MUSIC FADES IN]

So, to fill in the background here, Japan had launched a surprise attack on Hawaii in December of 1941.

[02:09] FDR: Mr. Vice President. Mr. Speaker.

[02:15] SV: The next day, the United States declared war.

[02:20] FDR: Yesterday, December 7th, 1941, a date which will live in infamy.

[02:30] SV: Now, shortly after that, in early 1942, FDR issued Executive Order 9066. That order let the military start detaining people of Japanese descent and hauling them off to sites all over the country.

[02:46] FDR: I have directed that all measures be taken for our defense.

[02:50] RA: Yeah. So our team also spoke recently about this practice of Japanese internment, really confinement, with one of the world’s foremost scholars of that era. And, Siva, he told us the government set up 10 so-called relocation centers. Really, they were concentration camps.

[03:07] Greg Robinson: Now, the word “concentration camp” is perfectly legitimate for talking about the time.

[03:12] RA: This is Greg Robinson.

[03:14] GR: That is, at the time before the Nazis made “concentration camps” a euphemism for death camps, it just meant a place where people were concentrated together. And it was not a very nice word, but it was not a horribly inhuman word. And Franklin Roosevelt himself twice used the phrase “concentration camps” to refer to the places where the Japanese Americans were being held.

[03:36] RA: And, you know, most of the people held in these camps were actually American citizens. They lost their homes, their belongings, they lost their communities. And this went on for three years until almost the end of the war. Here’s what Greg told our co-host Will Hitchcock about it.

[03:51] GR: I call it a “tragedy of democracy” — because it’s not like a mass atrocity, like slavery or the Holocaust or the treatment of Native Americans. It was carried out in humane fashion as best the government could. And yet, it’s shattered the lives of 100,000 and more people.

[04:17] Will Hitchcock: So, it turns out that democracies can imprison, wrongly, its own citizens. I take it that’s part of the tragedy here.

[04:24] GR: That’s exactly right. In a war fought for democracy and the preservation of democracy against fascism, a democratic country, and the leader of the forces for good in the world, actually rounded up its own citizens — really out of no reason but wartime hysteria, political opportunism. Very obvious flaws.

[04:51] RA: Not only that, Greg said, but in many cases, families were separated. And I’m wondering, Siva, if anything like that happened to Karen’s family?

[05:00] SV: Yeah, it did, and I’ll let her explain.

[05:02] KKI: At the very beginning, when the anti-Japanese hysteria was starting, usually the government rounded up the adult males first. So, on my mother’s side, my grandfather, who was a Christian minister, so leader of his community, was taken and taken to Crystal City, Texas, where he was incarcerated for most of the war. And then on my father’s side, his father was taken to New Mexico. So, both sides of the families, their fathers were separated from the rest of the family.

[05:27] SV: My gosh.

[MUSIC]

[05:33] RA: You know, I notice Karen and Greg both use the word hysteria. And that’s, like, really important to recognize in this story. The logic of Japanese confinement was national security, right? These people were supposedly a threat. They might be spies. They might sabotage military installations. That was the government’s position. But as Greg told us, there was virtually no evidence of this kind of subversion.

[05:57] GR: Roosevelt’s own informal team of spies reported back that Japanese Americans were 90-98% loyal and embarrassingly eager to prove their patriotism. But I think that the drumbeat of fake news and the economic interest of people on the West Coast — and also the military’s desire on the West Coast not to be caught with its pants down as their counterparts in Hawaii had been — all led to a climate of opinion where people were ready, even overprepared, to believe the worst about Japanese Americans, even in the face of the evidence. It’s ironic that even J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI, said that the Japanese Americans did not pose a security risk.

[06:39] SV: Yes, but let’s be blunt. We are talking in many, many cases about families that had been here for generations, and nothing like this had been done with German Americans or Italian Americans. So what was really going on here was racism.

[06:57] RA: Exactly. And we talked about this with Greg. The historical record on it is clear.

[07:01] GR: There’s anti-Japanese sentiment from the very beginning of Japanese settlement in the United States. As of 1908, there is basically a cut off of Japanese immigration. So the majority of the Japanese community on the mainland in 1941 are the children of these immigrants. The parents cannot become citizens. The children, in some cases, have to go to separate schools. They’re prevented from marrying whites, and they are excluded from civil service. For example, in California, there’s not a single Japanese American public schoolteacher in the years before World War II. Because of their racial heritage, they are subjected to discrimination by nativist groups and commercial groups. And after Pearl Harbor, these groups discover that they have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get rid of their hated rivals, and so they seize on it.

[08:00] RA: Siva, I’d love to get back to Karen Inkelas and her family history. I understand her parents were born in the United States.

[08:07] SV: Yes. Yes they were.

[08:08] RA: This experience must have been really traumatic and confusing for them. And at the same time, you know, one of the things Greg told us was that Japanese Americans struggled, heroically, to make the camps livable. They planted gardens. They held cultural events. There were classes in art and Japanese crafts. But also, he said, most of the time it was just incredibly boring. I mean, their lives were turned upside down and suddenly they were in prison. What was life like in the camps for Karen’s parents? You must have asked her about it.

[08:39] SV: Yeah, yeah. Look, this is very interesting. What she told me was that her parents, who later would meet in Chicago after the war, never really talked about life in the camps with her — like with no detail or elaboration while she and her siblings were growing up.

[08:56] KKI: There’s a great phrase in Japanese: Shikata ga nai. It roughly translates to “It can’t be helped.” And I think a lot of Japanese Americans felt that. I think that’s also emblematic of my parents: that something very bad happened to them in their past, but it wasn’t going to dictate the rest of their lives. They were going to move on, and then move on they did. And they didn’t look back. They never really ever talked about internment and what kind of effect it had on their lives.

[09:35] RA: Wow. Okay, so let me rewind just a bit, Siva. In late 1944, the camps, they start shutting down. People are released. They start to rebuild their lives. The war is still dragging on. It goes on into the following summer. What happened to Karen’s grandfathers? Were they reunited with their wives and their children?

[09:53] SV: Yeah, yeah, they were eventually. And like a lot of Japanese Americans at the time, both families received help from the American Friends Service Committee — the Quakers. The Quakers helped them find some jobs and find places to live and so forth. But the story of what happened to Karen’s father is really fascinating.

[10:14] RA: All right, well, why don’t we roll the conversation from there for a bit?

[10:17] KKI: So, after he left Poston, Arizona, and wound up in Chicago, he had to bounce around to several different high schools — because there were no schools in the camps, they had sort of a makeshift education. But he had to finish up courses. Everything was out of sequence. Eventually he graduated from high school, got a scholarship to go to college. This is also a much longer story, but he wound up at a little college called Elmhurst College in Elmhurst, Illinois. And in the fall of his freshman year, he was drafted by the U.S. Army. So, the same government who thought he wasn’t trustworthy enough to live on his own and saw fit to put him and his family in an internment camp, now was asking him to fight on behalf of the country.

[10:55] SV: Telling him to fight. Not even asking.

[10:57] KKI: Telling him to fight. Yeah. So, he, luckily, that was the very end of the war. He didn’t know at the time, obviously when he was drafted. But the war ended, and he served in the occupation forces in Okinawa.

[11:08] SV: Oh my gosh. Like they didn’t even send him to Europe?

[11:11] KKI: No, no. They sent him in the Pacific. Once again — ironic, isn’t it? —that they’re so afraid Japanese Americans were consorting with the enemy, but then they sent him to fight in the very place where the enemy was.

[11:23] SV: Wow. So, what did he make of that? Had he been to Japan?

[11:29] KKI: No. Never been to Japan. He spoke rudimentary Japanese enough to speak to his parents, but he wasn’t fluent by any stretch of imagination. He has photographs that he’s shown me, which are remarkable. And if you know what Okinawa looks like, it looks nothing like it. It’s just farmland in every direction and tropics. I don’t know that he — he’s never verbalized to me the irony of that. I think kind of Shikata ga nai. “Okay, I’ve been drafted. Now I have to serve.” And, you know, I have to figure out what to do with myself while I’m in the army kind of mentality. Don’t look back. Look forward.

[12:03] SV: Now, when you found out about these experiences, what was your sense of how they processed it?

[12:10] KKI: So, as I mentioned, they never really talked about it at all. I think the one legacy of their experience, though, is I do believe at some maybe even unconscious level, that they believed it was important in order to be in America, you needed to act like an American. And so, because of that, we grew up in a very American household: drove American cars, I watched American TV, never spoke a word of Japanese. We spoke English in the household.

[12:35] SV: You’re a Cubs fan?

[12:36] KKI: I’m a Cubs fan.

[12:37] SV: As if you haven’t suffered enough.

[12:39] KKI: Well, we did win once. And my father was alive to see. You know, I’m a Cub fan because of my father. You know, so I think that was part of my upbringing, because there might have been some sort of lingering legacy in their heads about how important it is to display Americanism or whatever you believe Americanism is.

That being said, I’m always amazed that my parents didn’t hold more resentment or bitterness toward the government for what happened to them. Maybe it’s Shikata ga nai? I also think it’s just they do love this country for whatever reason, and they passed that on to their children — so much so that I have an irreverent love for this country too because of them and what this place stands for. And I think it’s meaningful to think about in terms of how we’ve lived out our lives, my brother and sister and I — that we’re products of a family that went through with the Depression, internment and the war and came out where they are.

[MUSIC]

My father once said that although internment took away everything that he and his family had, the U.S. government gave it all back to him through the GI Bill.

[13:48] SV: Oh my gosh. So go deeper on that. So, he gets out of the military.

[13:53] KKI: He went back to college, funded by the GI Bill. The GI Bill also funded his medical school, and eventually he became a doctor. So, you know, I grew up in relative comfort, the daughter of a doctor, because the U.S. government paid for it. Now some would argue, “Yeah, but he had a fight in the war in order to get the GI Bill.” But my dad doesn’t think of it that way. He thinks that this was an enormous blessing that he was given by the government in order to live out his life the way he wanted to live it and provide for his family.

[14:21] SV: And he had done his duty as any young American man at that moment.

[14:25] KKI: Because that’s what was required of him as an American.

[14:27] SV: Right. Well, yeah. Wow.

So, when you found out about what your parents had gone through, how did that change you?

[14:41] KKI: At the time they told me, I don’t know that it necessarily resonated with me. It was much later, I think it coincided with, as I mentioned, I grew up in sort of a very Americanized kind of household, but I always knew I was different. I grew up in a predominantly white community, so it was starkly obvious that I was different than the other kids. I think I struggled a little bit with that about, well then who am I? And because we didn’t outwardly display our Japanese heritage, I decided, “Well, okay, when I go to college, I’m going to go full tilt.” So, I studied Japanese, I took Japanese history, I studied abroad in Tokyo for a year in order to find who I am in a very melodramatic, late adolescent way.

But when I was in Japan, I started to realize I’m not Japanese either. There were parts of that culture that didn’t jive with my Western sort of sense of ideology and who I was philosophy. So, I started realizing only after that very pivotal year in Japan that identity isn’t about fitting in. And in my case, my identity is about sticking out. I make my own identity. Nobody tells me what it is.

[MUSIC]

[15:56] RA: So, this question of identity. Yes, we make our own identities, but it’s also influenced by the way people think about you. The way people behave toward you. You know, this policy of Japanese confinement was completely rooted in xenophobia. We can’t escape that. That’s the fear of people who “stick out,” as she put it, for one reason or another. And so, I think it’s important to think about how that past has lessons for us today. There’s continued prevalence of racial and ethnic hatred in the United States, and there is a continual struggle to confront it.

[16:31] SV: Yeah, right. And, you know, look, one thing I know about Greg Robinson’s work is that he goes deep on this core tension of muscular American liberalism, like that of FDR. And we see this dynamic of a push toward liberty, equality and the rule of law. But it’s always constrained by and framed by nativism and other forms of bigotry, both soft and hard.

[16:58] RA: Yeah, Greg definitely goes there, and we asked him to go there. Will in particular was interested in this because he’s writing a book about FDR right now, and he kind of enlisted Greg in untangling this great paradox of Roosevelt’s agenda.

[BEGIN TWO-WAY: WILL WITH GREG ROBINSON]

[17:12] WH: Greg, in studying this so carefully, as you’ve done for many years, how do you reconcile a story of progressive policies of the New Deal from 1933 onward up through 1945, in this same era — Roosevelt sort of charting a new, almost a new Bill of Rights, if you like, for Americans’ access to a new network of social programs and employment and housing and so forth. With the persistence — not just in this case, but in many others — of profound institutional racism, how can we as students of history, but also as teachers, sort of weave together these two, what would appear to be, contradictory trends in the New Deal era?

[17:51] GR: That’s a wonderful question. And it’s one that you’re exactly right that I have been wrestling with ever since I was first writing what became my dissertation and my first book, By Order of the President, about Franklin Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066. Sometimes I couldn’t sleep. I would be so angry, or I would be so passionate about this very question. I felt almost betrayed by FDR when I found out about this. And then I, with time, I began to understand that Roosevelt’s prime objective was winning the war. And I don’t know, I don’t have insight into him, but it’s perfectly plausible that Roosevelt knew that there was no great threat from Japanese Americans. But the needs of the war mattered more to him than the rights of 100,000 people that he didn’t really think of as Americans in any sense. During the 1920s, Roosevelt had supported restriction of immigration of Japanese Americans and other Asian immigrants and the laws that prevented them from owning property, becoming citizens on the grounds, he said, that they protected the racial purity of whites against interracial marriage.

[18:57] WH: One thing I’m curious about is whether or not Japanese Americans attempted to oppose the relocation orders and if they had any kind of platform to do so, or if they had any allies in the civil liberties community in 1942. Was Pearl Harbor and the attack just so shocking that there was no opportunity to disagree publicly and to argue the point? Or were there those who stood up and said, “This is wrong,” even at the time?

[19:25] GR: There were a few people who stood up and said, “This is wrong.” At the time, Norman Thomas, the leader of the Socialist Party, organized petitions and had public events to challenge Executive Order 9066. Dorothy Day, the head of the Catholic Worker, wrote articles in The Catholic Worker about how horrible it was. There were a few voices — a Black attorney in California, Hugh MacBeth, fed information to Norman Thomas and tried to secure a meeting with Roosevelt to try and lobby against Executive Order 9066, using a White House cook as a backchannel. There were a few Japanese Americans who challenged in court the restrictions on them and the mass removal, leading to the Supreme Court cases of Fred Korematsu and Minoru Yasui and eventually Mitsuye Endo as well.

[20:14] WH: I wonder if you could walk us through that. What were her claims, and how did it gradually succeed in undermining the legal position of the government?

[20:23] GR: Mitsuye Endo was a government employee. She was fired from her job because she was Japanese American and then removed, and her lawyers with the American Civil Liberties Union, James Purcell, thought that the best way to get her her job back would be to challenge her confinement. But the government engaged in a certain amount of skullduggery. First, the ACLU, and Purcell particularly, brought a habeas corpus case to get her out of camp to challenge her confinement. And the judge in that case sat on it for ages and then finally dismissed it. The case eventually went to the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, the government offered Mitsuye Endo a ticket out of camp to go outside the West Coast if she would drop her case. But very bravely, she refused. She said: I can’t get my job back if I can’t get back to California. And I can’t get back to California if I abandon this case. So for the sake of everybody, I’m going to keep on it.

So eventually, the case came to the Supreme Court in 1944, at the same time that the Fred Korematsu case came challenging mass removal. The Supreme Court engaged in a great deal of hair splitting because they said that Fred Korematsu’s case only involved mass removal, not the confinement that followed afterwards. And so, they found that mass removal was constitutional — that is, they were not going to say that the army had acted illegally. Whereas in the case of Mitsuye Endo, they said that a concededly loyal citizen like Mitsuye Endo herself could not be kept in camp indefinitely. And this led the army to reopen the west coast and open up the camps for people to leave.

[22:27] WH: So in the 1980s, the US government finally acknowledges what it had done during the war as wrong. How significant was that moment for Japanese Americans and their families?

[22:39] GR: I think that the 1988 civil liberties law, which provided an official apology and a $20,000 redress payment to survivors of the camps — that is, not the families of people who had died, but just the people who were still living — was enormously important in the redress struggle, which allowed many Japanese Americans to talk for the first time about what they’d gone through during the war. And the government’s acknowledgment that it had wronged Japanese Americans, and that it had offered a terrible precedent, was very important. In the same way, the convictions of Fred Korematsu and Gordon Hirabayashi, which the Supreme Court had upheld, were reversed in federal court on the grounds of misconduct by the government. And so, again, that’s an enormous step for the government in acknowledging the wrongs that it had done. Of course, the $20,000 redress payment didn’t and couldn’t make up for the entire mass removal and confinement, but it was a symbol of reparation.

[MUSIC]

[23:50] SV: Robert, we often hear an upbeat story about the United States, right? How we’re a country of immigrants.

[23:57] RA: You and I are both part of this story.

[23:59] SV: And our families strive and survive, and you know, and rise. And, of course, that’s not untrue. But, you know, it’s also a country that seems to always put its more recent immigrants through the wringer. And that experience marks their lives and their descendants’ lives in really powerful ways. And as we have heard, Karen studied Japanese, and she lived briefly in Japan to try to find her roots. Now, later, as a scholar, she dedicated herself to studying higher education with all of its gateways and barriers to human flourishing.

[24:39] KKI: College is an extremely transformational time. And so, I wanted to make sure that everyone had the opportunity to have that kind of experience and not be robbed of it because of some systemic reason that it’s hardwired into the institution. So that’s really, I think, why I study what I study.

[24:55] SV: And even though her own parents didn’t talk much about the experience of confinement, one of the things Karen told me is that she is making an effort to talk to her own daughter about it, to help her daughter understand that past, her story, her role in America. Now, not that long ago, Karen and her family visited another symbol of reparations, so to speak, and I asked her what it might tell us about American attitudes toward immigrants more broadly.

[BEGIN TWO-WAY: SIVA WITH KAREN INKELAS]

SV: So recently, you were able to visit the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. What did you see? What did you experience? How did that affect you?

[25:39] KKI: Sure. I’ve actually been to the Japanese American Museum many times, but the last time I went, there was a new exhibit. There’s a book called “the Ireichō” which means “The Book of Names.” It’s a really large book, and it’s all the names of all the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II — where they invite the families of the folks who were in the book to come and place a stamp next to the names of their family members, with the hope that eventually every name will have a stamp. And so, I went last year, and I placed a stamp next to my mother’s name, my father’s name, my grandparents’ names, my aunts’ and uncles’ names. It was incredibly meaningful. And it still resonates in me. I feel so honored that I was the one that did that on behalf of my family. It was powerful.

And I think I heard that the Ireichō was going to start, now, traveling. So, it’ll leave L.A. in order to get to other parts where other people are, because I know one of their desires is to kind of stamp next every person’s name. But that’s going to be difficult because Japanese Americans, partly because of the war, have spread out all over the country now. And so, it’s going to need to travel across the country not only for that reason, but just to educate everyone about just how many names that is because it’s a large, large book of people who are incarcerated during the war.

There’s a particular thing that I thought about, actually, as I was piecing together and getting ready for this podcast. That exhibit, the book is in the center of the exhibit, and all around it are planks of wood with the names of the places that Japanese Americans were incarcerated. Not just the internment camps, but all the places: the detention centers, racetracks, whatever. There’s a lot of planks. More than I knew. In fact, there were four or five locations in Chicago — which I had no idea about, I didn’t know Chicago had any prisoners from that time period. On each plank is a little jar that has the dirt from that location. But it flanks the book. So on three sides of the exhibit, there are these planks of wood, which essentially resemble a wall. And in some ways it does seem symbolic about the fact that this book of names is flanked by all these locations and representing planks of wood. There’s something symbolic about how this also represents the way the Japanese Americans themselves were separated and isolated from everyone else.

[MUSIC]

[27:49] SV: Yes. There is no book of names for families from Central America who were forcibly separated over the past decade in this country. There was no database, apparently. The federal government lost children. When you reflect on your own family saga and the efforts it took for people to find each other and to establish lives and build your lives. And your family were not even immigrants — they were U.S. born citizens. What do you think it’ll take for us to heal from that infliction of pain on so many children, who might someday want to be in our classrooms?

[28:46] KKI: It’s heartbreaking, isn’t it? And I do think of internment, about where does anybody feel that they have the right to just summarily decide a whole group of people are guilty just because of who they are, not necessarily what they did? And the fact that we continue to keep doing it even after we’ve learned the lesson from internment. You know, we may not necessarily set up camps like we did during internment, but we’re clearly detaining people. We’ve seen the photographs at the border. I remember after 9/11, the calls to ban all Muslims and perhaps even incarcerate them to protect ourselves.

I’d like to think and hope that we will never return to internment camps again, thanks to the lesson we’ve learned from Japanese. But, you know, each day, I think my hope gets a little bleaker because we see more and more reminders of this sort of vitriol around who belongs here, which are the good countries for the people can immigrate from and which are not. This whole language is it’s frightening, and it’s just destructive. Yeah, I do think there’s part of me that resonates very strongly with it because of my family’s history.

[29:58] RA: So, Karen, obviously she has this very personal connection to that past. Greg is not Japanese American, but he’s studied it. He’s really dug deep. And so, we just had to ask him a similar question. What did he have to say about the implications of that past for contemporary immigration policy?

[30:18] GR: Well, of course, I’m more of an expert on the past than on the present. And when I speak about the present, I speak as a citizen, not as a historian. You know, the mass removal was popular, or at least not unpopular during the war. In large part, people in California approved it, and people in the rest of the country didn’t know or didn’t care, or thought the government knew what it was doing. It’s not that they actively approved, necessarily, but they took for granted that it was just and logical and necessary. And I do recognize many similarities, particularly the fact that the migrant children who are separated from their families are confined at Fort Sill, which is a place where Japanese Americans were held during the war. And yes, I think politics and public opinion plays a great deal in this kind of action by the government. And if people recognized the precedent of Japanese Americans and their unjust treatment, it would probably lead people to take a differing view.

[MUSIC]

[31:34] RA: That was Greg Robinson. He’s a professor of history at the University of Quebec in Montreal. He’s the author of numerous books on Japanese life in the United States and Canada, including A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America.

[31:49] SV: We also heard from Karen Kurotsuchi Inkelas. She teaches at the University of Virginia School of Education and Human Development, and she’s the research director of a project called Crafting Success for Underrepresented Scientists and Engineers. Karen has published on living learning communities and is the author of Racial Attitudes and Asian Pacific Americans: Demystifying the Model Minority.

[32:15] RA: That’s going to do it for this episode. In a couple of weeks, we’ll head to India, where a billion people are deciding the fate of self-government in the subcontinent.

[32:23] Radha Kumar: When it comes to dissent, the Modi administration began by first attacking universities.

[32:31] SV: In the meantime, we will post some bonus content in our feed — more from the conversations we had with Greg Robinson and Karen Inkelas.

[32:40] RA: You can also find all that and more on our web page, dindanger.org! And check out our Instagram account, @dindpodcast for behind-the-scenes reels from our studio.

[32:51] SV: Democracy in Danger is produced by Robert Armengol, Nicholas Scott, Stephen Betts, and Ariana Arenson. Adin Yager engineers the show. Our interns are Charlie Burns, Leena Fraihat, Katie Pile, Makhdum Mourad Shah, and Caroline Yu. We have help from Ellie Salvatierra.

[33:11] RA: Support comes from the University of Virginia’s College of Arts and Sciences. The show is a project of UVA’s Karsh Institute of Democracy. We’re part of The Democracy Group podcast network, and we’re distributed by the Virginia Audio Collective of TJ Radio in Charlottesville. I’m Robert Armengol.

[33:30] SV: And I’m Siva Vaidhyanathan. Until next time.

[MUSIC OUT]