The Plight of Pakistan

The followers of an ousted and jailed leader won the votes, but they won’t govern.

Read

Last May, protestors took to the streets in Pakistan to support Imran Khan, the populist prime minister tossed from office and into the slammer. Now, in a rebuke to the military and political establishment, voters put more candidates from Khan’s circle in parliament than from any other party. But they fell short of a majority last month in an election marred by vote-rigging. Siva speaks with an anthropologist in Karachi who parses the state of Pakistani politics and the country’s prospects for real democracy.

From 2018 to 2022, Imran Khan ruled Pakistan like every other recent prime minister — in the shadow of an opaque military machine. But he fell out of favor with the establishment and was removed from office in a first-ever vote of no-confidence. A year later, in May 2023, Khan was arrested on corruption charges, and many members of his party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf — or Pakistan Movement for Justice — were abducted and coerced into renouncing their allegiance to the PTI. If anything, however, Khan’s popularity has only grown, as he uses social media and even artificial intelligence to drum up his base from prison.

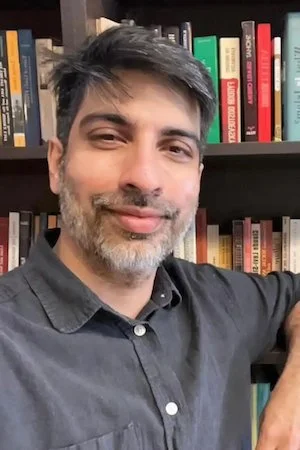

Our guest, Arsalan Khan, explains what this level of support for Imran Khan, a populist who rails against corruption, indicates about democratic sentiment in a country that has now had four national elections since the actual military rule of Gen. Pervez Musharraf ended in 2008.

Meet

Arsalan Khan is an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and an expert on Pakistani politics. He studies Islam, gender and ethics across South Asia. His first book is The Promise of Piety: Islam and the Politics of Moral Order in Pakistan (2024, Cornell University Press). Khan’s new research looks at climate justice in Karachi, where activist groups are connecting across class and caste to stake claims that draw on democratic as well as Islamic ideals. Follow him @akkhan81.

Khan writes in The Promise of Piety about practitioners of Tablighi Jamaat, a worldwide Islamic movement that focuses on a kind of face-to-face preaching known as dawat. The book is based on ethnographic fieldwork Khan conducted in and around urban Pakistan’s Tablighi mega-mosques.

Unlike other Muslim traditions in Pakistan, Tablighis reject explicitly political action in favor of self-reform and “pious companionship,” Khan says.

It’s true that corruption and state violence are at the root of Pakistan’s problems, Khan argues, but the problematic cult of personality that surrounds the country’s former leader is not the answer.

While serving as prime minister, Imran Khan sat for an interview with HBO in which he blamed sexual violence, in part, on women wearing provocative clothing. Arsalan Khan again took the Pakistani leader to task for this outlandish claim: “It is also a great irony,” he writes in an essay for Naya Daur, “that Imran Khan who is always decrying Islamophobia in the West has actually reinforced some of the worst stereotypes about Pakistani culture and Islam.”

In a 2019 piece in The Immanent Frame, Arsalan Khan tells a story from his time in the field — about a high school friend who let fly his rage upon an erratic Karachi driver. The experience highlighted for the anthropologist a paradox of Islam’s centrality in Pakistani public life. As Islamic authority grows, Khan says, “it also appears to Muslims to have been emptied of its ethical substance.”

Writing with Sara Eleazer, Khan has considered how accusations of blasphemy and threats of violence against Pakistani Christians serve not only to exclude but incorporate non-Muslims in the body politic — as “subordinates and dependents” within a national religious hierarchy.

Learn

Imran Khan’s rise to prominence in politics — after his glorious career in cricket — began in the mid-1990s, with his founding of the PTI. It took a while to get traction, but in 2018, the party won a near-majority of seats in parliament and formed a coalition government with Khan as prime minister.

After Khan’s arrest, widespread protests and clashes with police and the military resulted in multiple injuries and deaths. On social media, Khan had blamed his ouster on a U.S.-backed effort to remove him from office.

American leaders have denied any conspiracy. But citing a secret document, The Intercept reported last August that two officials of the U.S. State Department met with Pakistan’s ambassador to the United States to encourage Khan’s ouster.

In the so-called cypher case, Khan was accused of having a hand in leaking that document, resulting in a 10-year prison term, on top time he was already serving for a corruption conviction and a ban from public service. The latest sentence was handed down just weeks before this year’s elections.

Last week, one of the state department officials who reportedly pushed for the Pakistani government to can Khan testified about U.S.-Pakistan relations before the House foreign relations committee.

The Nation explains how the post-Khan crackdown sidelined the PTI in the election. Still, the party backed independent candidates, claiming a plurality of as many as 100 seats in the National Assembly. With no formal status, however, the PTI won’t be able to claim unelected seats reserved for women and minorities of each party.

Incoming prime minister Shebaz Sharif will have his hands full dealing with multiple crises. Despite agreeing to a coalition with Sharif’s Muslim League, the Pakistan People’s Party has said it won’t join the new government. Sharif and his cabinet will take power amid staggering inflation, longstanding human rights violations, cross-border attacks against Afghan insurgents and rising tensions between Pakistan’s two most powerful allies: the United States and China.

Heard on the show

We spiced the intro this time with some soundbites from news coverage of Pakistan’s election aftermath, drawing on Al Jazeera and CNN.

Transcript

Coming soon!