Telltale Coup

Did a 1934 scheme nearly topple the American Republic? This week: A history lesson for our times.

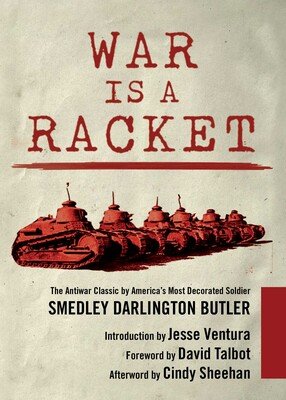

Just as FDR and his allies were crafting the New Deal, a retired Marine named Smedley Butler came forward with a shocking revelation. Powerful business interests, Butler alleged, were plotting to overthrow the U.S. government. Inspired by the rise of fascism in Europe, the conspirators had sought Butler’s aid. Little did they know, decades of fighting for American imperialism had left him disillusioned. So Butler blew the top on “the Business Plot.” Journalist Jonathan Katz helps Will and Siva unearth this bizarre tale.

The lesson in Butler’s story remains important today, as disastrous conflicts from Vietnam to Afghanistan continue to maim American ideals. After all, another decorated officer might have cut the other way, Katz says. Many soldiers returned from Vietnam and joined the peace movement. But veterans of such forever wars are just as easily radicalized, as evidenced in the disproportional number of Jan. 6 rioters with military backgrounds. If the United States continues to send young men and women to battle for the interests of capital, it may find itself — again and again — fighting its own demons at home.

Heard on the show

For some extra ambience, we selected a few tracks from the once-mysterious Podington Bear (a.k.a. Chad Crouch of Portland, Ore.). Here they are in the order they appeared: “Lamb and Wolf” (Said Lion to Lamb, 2018); “Am-Trans” (Electronic, 2016); “Climbing the Mountain” (Bon Voyage, 2015); and “Dark Matter” (Thoughtful, 2013).

We also dropped in some clips from Roosevelt’s speeches and Fireside Chats of the early 1930s. You can listen to a boatload of that audio online at the FDR Presidential Library and Museum. For the complete version of the March of Time newsreel on the Croix de Feu movement in France, stop by Alexander Street.